| Description Links |

The Classical Harp Description Page |

| Buy cd's at Amazon Buy sheetmusic at SheetMusicPlus |

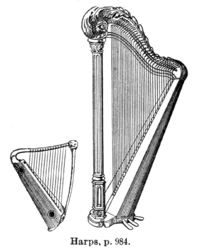

The 'harp' is a stringed instrument which has the plane of its strings positioned perpendicular to the soundboard. It is classified as a chordophone by the Harvard Dictionary of Music and only types of harps are in that class of instruments with plucked strings. All harps have a neck, resonator, and strings. Some, known as frame harps, also have a forepillar; those lacking the forepillar are referred to as open harps. Depending on its size (which varies considerably), a harp may be played while held in the lap or while it stands on the floor. Harp strings are made of nylon, gut, wire, or silk on certain instruments. A person who plays the harp is called a harpist or harper. Folk musicians often use the term "harper", whereas classical musicians use "harpist".[citation needed] Various types of harps are found in Africa, Europe, North, and South America, and in Asia. In antiquity, harps and the closely related lyres were very prominent in nearly all cultures. The oldest harps found thus far have been uncovered in ruins from ancient Sumer. The harp also predominant in the hands of medieval bards, troubadors and minnesingers, as well as throughout the Spanish Empire. Harps continued to grow in popularity through improvements in their design and construction through the beginning of the 20th century. The aeolian harp (wind harp), the autoharp, and all forms of the lyre and Kithara are not harps because their strings are not perpendicular to the soundboard; they are part of the zither family of instruments along with the piano and harpsichord. In blues music, the harmonica is called a "Blues harp" or "harp", but it is a free reed wind instrument, not a stringed instrument, and is therefore not an actual harp.[citation needed]

OriginsHarps were most likely independently invented in many parts of the world in remote prehistory.[clarification needed] It is self-evident that the harp's origins may lie in the sound of a plucked hunter's bow string or the strings of a loom. A type of harp called a 'bow harp' is nothing more than a bow like a hunter's, with a resonating vessel such as a gourd fixed somewhere along its length. To allow a greater number of strings, harps were later made from two pieces of wood attached at the ends: this type is known as the 'angle harp'.[citation needed]They can also come in different colours. The oldest depictions of harps without a forepillar are from 4000 BC in Egypt[citation needed](see Music of Egypt) and 3000 BC in Persia (see Music of Iran).[citation needed] Other ancient names for harps include magadis and sambuka. The kanun is a descendant of the ancient Egyptian harp and was introduced to Europe by the Moors during the Middle Ages but is like the beforementioned Aeolian harp not a harp but a member of the zither family.[citation needed] Structure and mechanismHarps are roughly triangular and are usually made primarily of wood. The lower ends of the strings are fastened to the inside of the sounding-board, which is the outer surface of the resonating cavity. The body is hollow and resonates, projecting sound both toward the player through openings, and outward through the highly flexible sounding board. The crossbar, or neck, contains the mechanism or levers which determine the pitch alteration (sharps and flats) for each string. The upper ends of the strings are attached to pins in holes drilled through the neck. The longest side, the column, encloses the rods controlling the mechanism of a pedal harp. At the base are seven pedals, which activate the rods when they are downwardly pressed. The modern sophisticated instrument spanning 6½ octaves in virtually all keys was perfected by the 19th-century French maker Sébastien Érard.[citation needed] Lever harps do not have pedals or rods. Instead they use a shortening lever on the neck for each individual string which must be activated manually in order to shorten the string and raise the tone a half step. Thus, a string tuned to natural may be played in sharp, but not flat. A string tuned to flat may be played in natural, but not sharp. Lever harps are considerably lighter in weight than pedal harps and are smaller in size and number of strings. Lever harps are popular for playing folk music and are most commonly called folk harps.[citation needed] The harp lute or dital harp adapts the lever tuning system to a fretted instrument in the lute or guitar family.[citation needed] Development and history in EuropeAngle harps and bow harps continue to be used up to the present day. In Europe, however, a further development took place[when?]: adding a third structural member, the pillar, to support the far ends of the arch and sound box. The 'Triangular Frame harp' is depicted in manuscripts and sculpture from about the 8th century AD, especially in North-West Europe, although specific nationalistic claims to the invention of the triangular frame harp cannot be substantiated.[citation needed] The graceful curve of the harp's neck is a result of the proportional shortening of the basic triangular form so that the strings are equidistant. If the strings were proportionately distanced, the strings would be farther and farther apart. European harps in medieval and Renaissance times usually had a bray pin fitted to make a buzzing sound when a string was plucked. By the baroque period, in Italy and Spain, more strings were added to allow for chromatic notes; these were usually in a second line of strings. At the same time[when?] single-row diatonic harps continued to be played.[citation needed] The first primitive form of pedal harps were developed in the Tyrol region of Austria. Hochbrucker was the next to design an improved pedal mechanism, followed in succession by Krumpholtz, Nadermann, and the Erard company, who came up with the double mechanism. In Germany in the second half of the 17th century, diatonic single-row harps were fitted with manually turned hooks which fretted individual strings to raise their pitch by a half step. In the 18th century, a link mechanism was developed connecting these hooks with pedals, leading to the invention of the single-action pedal harp. Later, a second row of hooks was installed along the neck to allow for the double-action pedal harp, capable of raising the pitch of a string by either one or two half steps. The idea was even extended to triple-action harps, but these were never common. The double-action pedal harp remains the normal form of the instrument in the Western classical orchestra. There was a chromatic harp developed in the late 19th century that only found a small number of proponents, and was mainly taught in Belgium.[citation needed] Latin AmericaIn Latin America, harps are widely but sparsely distributed, except in certain regions where the harp traditions are very strong. Such important centers include Mexico, Andes, Colombia, Venezuela, and Paraguay. They are derived from the Baroque harps that were brought from Spain during the colonial period.[citation needed] Detailed features vary from place to place. Paraguayan harps and harp music have gained a worldwide reputation, with international influences alongside folk traditions. Mexican "jarocha" harp music of Veracruz has also gained some international recognition, evident in the popularity of "la bamba". In southern Mexico (Chiapas), there is a very different indigenous style of harp music. Travel between the ports of Veracruz and Venezuela afforded an opportunity for transmission of harp traditions between these areas.[citation needed] In Venezuela, there are two distinct traditions, the arpa llanera and the arpa central (or arpa mirandina). The modern Venezuelan arpa llanera has 32 strings of nylon (originally, gut). The arpa central is strung with wire in the higher register. An authoritative source in Spanish is Fernando Guerrero Briceno, El Arpa en Venezuela (The Harp in Venezuela).[citation needed] The style of music and the manner of construction are differentiated from one region to another.[clarification needed][citation needed] Paraguayan harps have a wide and deep soundbox which tapers to the top. Like Baroque harps, but unlike modern Western harps, they do not stand upright when unattended. The harp is Paraguay's national instrument. It has about 36 strings. Its spacing is narrower and tension lighter than that of modern Western harps. It is played mostly with the fingernails.[citation needed] AfricaThere are many different kinds of harp in Africa. They do not have forepillars and so are either bow harps or angle harps. As well as true harps such as Mauritania's ardin, there are a number of instruments that are difficult to classify, often being labelled harp-lutes. Another term for them is spike harps. The West African kora is the best known. The strings run from a string arm to a 'spike' and the resonating chamber is attached to the base of the spike.[citation needed] AsiaIn Asia, there are very few harps today, though the instrument was popular in ancient times; in that continent, zithers such as China's guzheng and guqin and Japan's koto predominate. However, a few harps exist, the most notable being Burma's saung-gauk, which is considered the national instrument in that country. There was an ancient Chinese harp called konghou; the name is used for a modern Chinese instrument which is being revived. Turkey had a nine-string harp called the çeng that has also fallen out of use.[citation needed] Modern European and American instrumentsPlaying style of the European-derived instrumentMost European-derived harps have a single row of strings with strings for each note of the C Major scale (over several octaves). Harpists are aided in telling which strings they are playing because all F strings are black or blue and all C strings are red, and the wire strings are silver or bronze if C or F. The instrument rests between the knees of the harpist and along their right shoulder. The Welsh triple harp and early Irish and Scottish harps, however, are traditionally placed on the left shoulder (in order to have it over the heart).[citation needed] The first four fingers of each hand are used to pluck the strings; the little fingers are too short and cannot reach the correct position without distorting the position of the other fingers, although on some folk harps with light tension, closely spaced strings, they may occasionally be used. Plucking with varying degrees of force creates dynamics. Depending on finger position on the string, different tones can be produced: a full sound in the middle of the string, and a nasal, guitar-like sound at the very bottom of the string. Tone is also affected by the skin of the harpist, how much oil and moisture it contains, and the amount of thickening by callous formation and its surface texture. Concert harpMain article: Pedal harp

The concert harp is large and technically modern, designed for classical music and played solo, as part of chamber ensembles, and in symphony orchestras as well as in popular commercial music. It typically has six and a half octaves (46 or 47 strings), weighs about 80 pounds (36 kg; 5.7 st), is approximately 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) high, has a depth of 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in), and is 55 centimetres (22 in) wide at the bass end of the soundboard. The notes range from three octaves below middle C (or the D above) to three and a half octaves above, usually ending on G. Using octave designations, the range is C1 or D1 to G7. At least one manufacturer gives the harp a 48th string, a high A. The concert harp is a pedal harp. Pedal harps use the mechanical action of pedals to change the pitches of the strings. There are seven pedals, each affecting the tuning of all strings of one letter-name, and each pedal is attached to a rod or cable within the column of the harp, which then connects with a mechanism within the neck. When a pedal is moved with the foot, small discs at the top of the harp rotate. The discs are studded with two pegs that pinch the string as they turn, shortening the vibrating length of the string. The pedal has three positions. In the top position no pegs are in contact with the string and all notes are flat; thus the harp's native tuning is to the scale of C-flat major. In the middle position the top wheel pinches the string, resulting in a natural, giving the scale of C major if all pedals are set in the middle position. In the bottom position another wheel is turned, shortening the string again to create a sharp, giving the scale of C-sharp major if all pedals are set in the bottom position. Many other scales, both diatonic and synthetic, can be obtained by adjusting the pedals differently from each other; also, many chords in traditional harmony can be obtained by adjusting pedals so that some notes are enharmonic equivalents of others, and this is central to harp technique. In each position the pedal can be secured in a notch so that the foot does not have to keep holding it in the correct position. This mechanism is called the double-action pedal system, invented by Sébastien Érard in 1810. Earlier pedal harps had a single-action mechanism that allowed strings to play sharpened notes. Lyon and Healy, Camac Harps, Venus Harps, and other manufacturers also make electric pedal harps. The electric harp is a concert harp with piezoelectric pickups at the base of each string and an amplifier. Electric harps can be a blend of electric and acoustic, with the option of using an amplifier or playing the harp just like a normal pedal harp, or can be entirely electric, lacking a soundbox and being mute without an amplifier. The tension of the strings on the sound board is roughly equal to 10 kN (a ton-force) or 2,000 pounds. The lowest strings are made of copper or silver-over-silk over steel, the lower-middle strings of gut (from sheep or cows) and the upper-middle or highest of nylon. TechniqueThe harp is played with the fingertips, with force from the hand and arm, and ultimately the upper body. The fingertips are drawn in to meet the palm of the hand, thus releasing the string from whatever pressure was placed upon it by the fingers. The fingers are naturally curved or rounded as they touch the strings, and the thumb is gently curved as the tip rises to the string as an arc from its base. There are differing schools of technique for playing the harp. The largest are the various French schools, and there are specific Russian schools, Viennese and other schools from differing regions of Europe. One is called the Attl technique after Kajetan Attl, in which apparently only the uppermost parts of the fingers move and the hand is largely still. There is a St. Petersburg school (more than one) in Russia in which the thumbs are moved in a circular fashion rather than in and out toward the hand. The differences between the French schools lie in the posture of the arms, the shape of the hand and the musical aesthetics. The traditional French schooling calls for the right arm to be lightly rested against the harp using the wrist to sometimes bring the hand only away from the string. The left arm moves more freely. The hands are more-or-less rounded, though the thumb is usually in a low position relative to the hand. Finger technique and control are the emphasis of the technical approach, with extensive use of exercises and etudes to develop this. Musical choices tend to be conservative, and centered in the harp music of the 19th century, a continuation, if you will, of the salon tradition of harp playing. Two very influential 20th-century teachers of this approach were Henriette Renie and Marcel Grandjany. Grandjany's pupils have sometimes added to their technique the habit of having the knuckle joints curved inward rather than outward, optionally or always, as M. Grandjany's fingers were wont to do. The other major French school is the Salzedo school, developed by Carlos Salzedo, who studied with Alphonse Hasselmans at the Paris Conservatoire. Also a virtuoso pianist, he informed his harp playing with what came naturally as a crossover from his piano training. This resulted in a more curved hand, more free movements of the arms, a more wide range of dynamics and tone colors in his playing, which was exceptionally brilliant. He emphasized brilliance and speed in playing. He was also a dedicated modernist, oriented to contemporary music and ideas, and in the forefront of the same. He was an inspiring teacher, and his students filled many important teaching, solo and orchestral positions in the United States and elsewhere. He has come to be seen as American because he was exported to America to serve Arturo Toscanini as harpist at the Metropolitan Opera, and based his later career in the U.S. He helped to design two important harps, the Style 11 and the Salzedo model of Lyon and Healy harps. As an innovative performer and composer, he was of great influence on the direction of harp music composing. His own music began in a fluent late-Romantic style, then a unique Impressionist style and a modernist style unlike any other composer. In fact, he was more imitated by composers than imitative. Use in musicThe harp found its early orchestral use in concerti by many baroque classical composers (Handel, J. C. Bach, Mozart, Albrechtsberger, Schenck, Dussek, Spohr) and in the opera houses of London, Paris and Berlin and most other capitals. It began to be used in symphonic music by Hector Berlioz but he found performances frustrating in such countries as Germany where qualified harpists and harps were few to be found. Franz Liszt was seminal in finding uses for the harp in his orchestral music, and Mendelssohn and Schubert used it in theatrical music or oratorios. The French and Russian Romantic composer particularly expanded its symphonic use. In opera, the Italian composers used it regularly, and Puccini was a particular master of its expressive and coloristic use. Debussy can be said to have put the harp on the map in his many works that use one or more harps. Tchaikovsky also was of great influence, followed by Rimsky-Korsakov, Richard Strauss and Wagner. The greatest influence on use of the harp has always been the availability of fine harps and skilled players, and the great increase of them in the U.S. of the 20th century resulted in its spread into popular music. The first harpist known to play jazz was Casper Reardon, a pioneer in the world of "hot" music. Florence Wightman was likely the first to have her own radio series of recitals on several networks in the 1930s. Many passages for solo harp can be found in 19th century ballet music, particularly in scores for the ballets staged for the Mariinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg, where the harpist Albert Zabel played in the orchestra. In ballet, the harp was utilized to a great extent in order to embellish the dancing of the ballerina. Elaborate cadenzas were composed by Tchaikovsky for his ballets The Nutcracker and The Sleeping Beauty; as well as Alexander Glazunov for his score for the ballet Raymonda. In particular, the scores of Riccardo Drigo contained many pieces for harp in such works as Le Talisman (1889), Le Réveil de Flore (1894) and Les Millions d'Arlequin (1900). Cesare Pugni wrote extensively for the harp as well—his ballet Éoline, ou La Dryade included music written for harp to accompany the ballerina's numerous variations and enhance the atmosphere of the ballet's many fantastical scenes. Ludwig Minkus was celebrated for his harp cadenzas, most notably the Variation de la Reine du jour from his ballet La Nuit et le Jour (1881), the elaborate entr'acte composed for Albert Zabel from his ballet Roxana (1878), and numerous passages found in his score for the ballet La Bayadère, which in some passages were used to represent a veena which was used on stage as a prop. The French ballet composers were no slouches in the harp department, either. Delibes made excellent use of it, as did Gounod and Massenet in their music. There is a prominent harp part in "She's Leaving Home" by The Beatles in their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. In the 1970s, a harp was common in popular music, and can be heard in such hits as Cher's Dark Lady and the intro of Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves. Most often this was played by Los Angeles studio harpist Gayle Levant, who has played on hundreds of recordings. In current pop music, the harp appears relatively rarely. Joanna Newsom, Dee Carstensen, Darian Scatton, Habiba Doorenbos, and Jessa Callen of The Callen Sisters have separately established images as harp-playing singer-songwriters with signature harp and vocal sounds. Canadian singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan plays the harp in her 2006 holiday album, Wintersong. In Hong Kong, a notable example of harp in pop music is the song Tin Shui Walled City (天水圍城) performed by Hacken Lee with harp played by Korean harpist Jung Kwak (Harpist K). Harp use has recently expanded in the "alternative" music world of commercial popular music. A pedal harpist, Ricky Rasura, is a member of the "symphonic pop" band, The Polyphonic Spree. Also, Björk sometimes features acoustic and electric harp in her work, often played by Zeena Parkins. Philadelphia based Indie Pop Band Br'er uses a pedal harp as the foundation for their cinematic live sets. Art in America was the first known rock band featuring a pedal harp to appear on a major record label, and released only one record, in 1983. The pedal harp was also present in the Michael Kamen and Metallica concert and album, S&M, as part of the San Francisco Symphony orchestra. R&B singer Maxwell featured harpist Gloria Agostini in 1997 on his cover of Kate Bush's "This Woman's Work". On his 7th solo album Finding Forever, Hip- Hop artist Common features harpist Brandee Younger on the introductory track, followed by a Dorothy Ashby sample from her 1969 recording of The Windmills of Your Mind. Some Celtic-pop crossover bands and artists such as Clannad and Loreena McKennitt include folk harps, following Alan Stivell's work. Recently Florence Welch has begun to incorporate harps into her songs, notably on "Rabbit Heart (Raise It Up)".The Webb Sisters from UK use different size harps in almost all their material during live performances. See the List of compositions for harp for the names of some notable pieces from the classical repertoire. Harp PlayersPerhaps one of the most memorable harpists of the 20th century was Harpo Marx, whose stage name was taken from his proficiency with the instrument. Alan Stivell is a well-known crossover and Celtic harpist. He first recorded an EP record, "Musique Gaélique," in 1959, then an LP in 1964 called "Telenn Geltiek " (available in CD). Following these, he has released 21 other albums including his harps, from 1970 until now (the last one is "Explore" - 2006- ). He also recorded some albums especially dedicated to the harp: the famous Renaissance of the Celtic Harp (1972), "Harpes du Nouvel Age" (1985), and "Beyond Words" (2002). He helped to promote developments in Electro-acoustic and Electric harps.[2] Other famous harpists include Giuliana Albisetti, Clelia Gatti Aldrovandi, Claudia Antonelli, Lucia Bova, Sophia Corri, Ossian Ellis, Alice Giles, Felix Godefroid, Marcel Grandjany, Maria Vittoria Grossi, Alphonse Hasselmans, Ursula Holliger, Pierre Jamet, Alfredo Kastner, Johann Baptist Krumpholtz, Judy Loman, Ludovico, Maria Antonietta d'Asburgo-Lorena regina di Francia, François-Josef Naderman, Jean-Henry Naderman, Elias Parish Alvars, John Parry, Laura Peperara, Marie Thérèse Petrini, Franz Petrini, Fabrice Pierre, Francis Pierre, Franz Poenitz, Francesco Pollini, Henriette Renié, Roslyn Rensch, Carlos Salzedo, Dorette Scheidler, Anne-Marie Steckler (M.me Krumpholtz), Luigi Maurizio Tedeschi, Marcel Tournier, Mirella Vita, Albert Heinrich Zabel, Nicanor Zabaleta, Elena Zaniboni.[3]

Harpist Joanna Newsom onstage in 2007

Folk, lever, and Celtic instrumentsThe folk harp or Celtic harp is small to medium-sized and usually designed for traditional music; it can be played solo or with small groups. It is prominent in Welsh, Breton, Irish, Scottish and other Celtic cultures within traditional or folk music and as a social and political symbol. Often the folk harp is played by beginners who wish to move on to the pedal harp at a later stage, or by musicians who simply prefer the smaller size or different sounds. Alan Stivell, with his father Jord Cochevelou (who recreated the Breton Celtic harp), were at the origin of the revival of the Celtic harp (in the 70s).[2] The folk or lever harp ranges in size from two octaves to six octaves, and uses levers or blades to change pitch. The most common size has 34 strings: Two octaves below middle C and two and a half above (ending on A), although folk or lever harps can usually be found with anywhere from 19 to 40 strings. The strings are generally made of nylon, gut, carbon fiber or fluorocarbon, or wrapped metal, and are plucked with the fingers using a similar technique to the pedal harp. Folk harps with levers installed have a lever close to the top of each string; when it is engaged, it shortens the string so its pitch is raised a semitone, resulting in a sharped note if the string was a natural, or a natural note if the string was a flat. Lever harps are often tuned to the key C or E-flat. Using this scheme, the major keys of E-flat, B-flat, F, C, G, D, A, and E can be reached by changing lever positions, rather than re-tuning any strings. Many smaller folk harps are tuned in C or F, and may have no levers, or levers on the F and C strings only, allowing a narrower range of keys. Blades and hooks perform almost the same function as levers, but use a different mechanism. The most common type of lever is either the Camac or Truitt lever although Loveland levers are still used by some makers. One of the attendant problems with lever harps is the potential loss of quality when the levers are used. The Teifi semi tone developed by Allan Shiers is a development from traditional mechanisms and nips up the string with two forks similarly to a concert harp. The semi tone is double locking for a full clear sound and does not wear the string. It is machined from solid brass and hardened steel and is adjustable by an eccentric roller to suit any gauge of string. In addition, the whole unit can be moved up or down to affect perfect pitch and string alignment. The lever arms are coloured for ease of note recognition and two sizes are made to suit treble, mid and bass. Electric instrumentsMain article: Electric harp

Amplified (electro-acoustic) and solid body electric lever harps are produced by many harpmakers at this time, such as Lyon and Healy Harps out of Chicago, Salvi Harps out of Italy, and Camac Harps out of France. The Laser harp is also not a stringed instrument; it is a harp-shaped electronic instrument with laser beams where harps have strings. Wire-strung instruments ("clàrsach" or "cláirseach")Main article: Clàrsach

The Scottish medieval clàrsach 'Queen Mary harp' 'Clàrsach na Banrigh Màiri, (c.1400) [4] now in the Museum of Scotland, is a one of only three surviving medieval Gaelic harps.

The Gaelic triangular, wire-strung harp has always been known by the feminine term cruit but by 1204 was certainly known by the masculine term 'clàr' (board) and, by the 14th century, by the feminine form of 'clàr', i.e., 'clàirseach/clàrsach'. (Gd.) Clàirseach/clàrsach is a compound word, feminine in gender and composed of the masculine word 'clàr' (board/harp) and the feminising suffix '-search/-sach'. The suggestion that it is composed of the elements 'clàr' (board) and 'shoileach' (willow) is a much less likely explanation as i) the 'clàr shoileach' term is masculine in gender, taking the masculine form of the definite article, and ii) the /s/ phoneme is absent (replaced by an /h/ phoneme) and therefore the /l/ phoneme would be more likely to form part of any contraction (e.g., clàirleach). The origins of the Gaelic triangular harp go back at least to the first millennium. There are several stone carvings of triangular harps from the 10th century, many of which have simple triangular shapes, generally with straight pillars, straight string arms or necks, and soundboxes. There is stone carving evidence that the lyre and/or perhaps a non-triangular harp were present in Ireland[citation needed] during the first millennium. Evidence for the triangular harp in Gaelic/Pictish Scotland dates from the 9th century.[5] The harp was the most popular musical instrument in later medieval Scotland and Ireland and Gaelic poets portrayed their Pictish counterparts as very much like themselves.[6]

The harp played by the Gaels of Scotland and Ireland between the 11th and 19th centuries was certainly wire-strung. The Irish Maedoc Book Shrine dates from the 11th century, and clearly shows a harper with a triangular framed harp including a "T-Section" in the pillar. The Irish word lamhchrann came into use at an unknown date to indicate this pillar which would have supplied the bracing to withstand the tension of a wire-strung harp. The Irish and Highland Harps by Robert Bruce Armstrong is an excellent book describing these ancient harps. There is historical evidence that the types of wire used in these harps are iron, brass, silver, and gold. Three pre-16th century examples survive today; the Brian Boru harp in Trinity College, Dublin, and the Queen Mary and Lamont Harps, both in Scotland. One of the largest and most complete collections of 17th century harp music is the work of Turlough O'Carolan, a blind, itinerant Irish harper and composer. At least 220 of his compositions survive to this day. Since the 1970s, the tradition has been revived. Alan Stivell's Renaissance de la Harpe Celtique (perhaps the best-seller harp album in the world), using mainly the bronze strung harp, and his tours, have brought the instrument into the ears and the love of many people.[2] Ann Heymann has revived the ancient tradition and technique by playing the instrument as well as studying Bunting's original manuscripts in the library of Queens University, Belfast. Katie Targett-Adams ( KT-A) is currently leading the modern day crossover movement for the clarsach, performing to mainstream audiences across the globe, notably China. Other high profile players include Patrick Ball, Cynthia Cathcart, Alison Kinnaird, Bill Taylor, Siobhán Armstrong and others. As performers have become interested in the instrument, harp makers ("luthiers") such as Jay Witcher, David Kortier, Ardival Harps, Joël Herrou and others have begun building wire-strung harps. The traditional wire materials are used, however iron has been replaced by steel and the modern phosphor bronze has been added to the list. The phosphor bronze and brass are most commonly used. Steel tends to be very abrasive to the nails. Silver and gold are used to get high density materials into the bass courses of high quality clàrsachs to greatly improve their tone quality. In the period, no sharping devices were used. Harpers had to re-tune strings to change keys. This practice is reflected by most of the modern luthiers, yet some allow provisions for either levers or blades. Multi-courseA multi-course harp is a harp with more than one row of strings. A harp with only one row of strings is called a single-course harp. A double-strung harp consists of two rows of diatonic strings one on either side of the neck. These strings may run parallel to each other or may converge so the bottom ends of the strings are very close together. Either way, the strings that are next to each other are tuned to the same note. Double-strung harps often have levers either on every string or on the most commonly sharped strings, for example C and F. Having two sets of strings allows the harpist's left and right hands to occupy the same range of notes without having both hands attempt to play the same string at the same time. It also allows for special effects such as repeating a note very quickly without stopping the sound from the previous note. A triple harp features three rows of parallel strings, two outer rows of diatonic strings, and a center row of chromatic strings. To play a sharp, the harpist reaches in between the strings in either outer row and plucks the center row string. Like the double-strung harp, the two outer rows of strings are tuned the same, but the triple-strung harp has no levers. This harp originated in Italy in the 16th century as a low headed instrument, and towards the end of 17th century it arrived in Wales where it developed a high head and larger size. It established itself as part of Welsh tradition and became known as the Welsh harp (telyn deires, "three-row harp"). The traditional design has all of the strings strung from the left side of the neck, but modern neck designs have the two outer rows of strings strung from opposite sides of the neck to greatly reduce the tendency for the neck to roll over to the left. The cross-strung harp consists of one row of diatonically tuned strings and another row of chromatic notes. These strings cross approximately in the middle of the string without touching. Traditionally the diatonic row runs from the right (as seen by someone sitting at the harp) side of the neck to the left side of the sound board. The chromatic row runs from the left of the neck to the right of the sound board. The diatonic row has the normal string coloration for a harp, but the chromatic row may be black. The chromatic row is not a full set of strings. It is missing the strings between the Es and Fs in the diatonic row and between the Bs and Cs in the diatonic row. In this respect it is much like a piano. The diatonic row corresponds to the white keys and the chromatic row to the black keys. Playing each string in succession results in a complete chromatic scale. An alternate form of the cross-strung, the 6/6 or isomorphic cross-strung, has 6 strings on each side of the cross instead of 5 on one and 7 on the other. This configuration is less intuitive to someone coming from a piano/organ background, but more intuitive to someone with a guitar/violin or other chromatic or whole-tone instrument background because it utilizes a chromatic scale or wholetone scale. This configuration gives the entire octave in only 6 strings per side, making more efficient use of the size of the instrument. As a symbolPolitical

The Irish €1 coin

See also: Coat of Arms of Ireland, Coat of arms of Montserrat, Royal Standard of the United Kingdom, and Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom

The harp has been used as a political symbol of Ireland for centuries. Its origin is from the time of Brian Boru, a famous 'High King' of the whole island of Ireland who played the harp. In Celtic society every clan would have a resident harp player who would write songs in honour of the leader. These were called Planxties. This evolved and would eventually be adapted as a symbol and representation of the Kingdom of Ireland from 1542. It was used to symbolize Ireland in the Royal Standard of King James VI/I of Scotland, England and Ireland in 1603 and had continued to feature on all English, British and United Kingdom Royal Standards ever since, though the style of harp used differed on some Royal Standards. It was also used on the Commonwealth Jack of Oliver Cromwell, issued in 1649 and on the Protectorate Jack issued in 1658 as well as on the Lord Protector's Standard issued on the succession of Richard Cromwell in 1658. The harp is also traditionally used on the flag of Leinster. From 1922, the Irish Free State continued to use a similar harp, facing left, as its state symbol on the Great Seal of the Irish Free State, featuring it both on the coat of arms and on the Irish Presidential Standard and Presidential Seal - as well as on various other official seals and documents. This was based on the Trinity College Harp in the Library of Trinity College Dublin, which was badly restored in the 1840s. Since it was fully rebuilt in 1961, it is seen to be wider at the base of the soundbox but this has gone unnoticed by Irish officials.[8] The harp also appears on Irish coinage from the Middle Ages to the current Irish. A South Asian version of harp known in Tamil as 'yaal', is the symbol of City of Jaffna, Sri Lanka, whose legendary root originates from a harp player. CorporateThe harp is also used extensively as a corporate logo — both private and government organisations. For instance; Ireland's most famous drink, Guinness, also uses a harp, facing right and also less detailed than the state arms. This was the second London-registered trademark in the 1860s, but was not used until the 1870s, when it was placed on bottles of stout exported to Britain, in the hope that British consumers would associate the drink with wholesome Irish agricultural produce. It was adopted on Guinness products in Ireland from the 1890s, for a different reason; to remind supporters of the growing nationalist movement that Guinness was Irish.[9] A simplified harp was adopted in the 1990s. Relatively new organizations also use the harp, but often modified to reflect a theme relevant to their organization, for instance; Irish airline Ryanair uses a modified harp, and the Irish State Examinations Commission uses it with an educational theme. The harp is also used as the logo for League of Ireland football team Finn Harps, who are Donegal's senior soccer club. Other organizations in Ireland use the harp, but not always prominently; these include the National University of Ireland and the associated University College Dublin, and the Gaelic Athletic Association. In Northern Ireland the Police Service of Northern Ireland and Queen's University of Belfast use the harp as part of their identity. See also

Related categoriesReferences

Additional sources

External links

Celtic harp

| |||||||||||||||||||||

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Harp". Allthough most Wikipedia articles provide accurate information accuracy can not be guaranteed. | |||||||||||||||||||||

Help us with donations or by making music available!

©2023 Classic Cat - the classical music directory

Sousa, J.P.

Stars and Stripes Forever, the

US army Band “Pershing's Own”

Bach, C.P.E.

Solfeggietto in C minor

Marcelo Góes Alves da Silva

Mozart, W.A.

10 piano var. "Unser dummer Poebel meint"

Andor Foldes

Haydn, F.J.

10 Menuets for piano

Ed Faulk

Haydn, F.J.

Trio in D major H15:16

Mstislav Rostropovich

Liszt, F.

Liebesträume: 3 Notturnos

Alberto Cobo